The Yoshidaguchi Climbing Trail starts in Fujiyoshida City at Kitaguchi Hongu Fuji Sengen Shrine. After tying up your laces and adjusting your pack, soak up the atmosphere amidst towering trees and then offer some prayers to Konohanasakuya Hime no Mikoto, the principal deity of the holy peak and patron goddess of fires and childbirth.

With her blessing and a full bottle of purely refreshing magma-filtered water from the dragon spring in her front yard, head to the southwest corner of the temple grounds, up a series of stone steps, and through a plain wooden tori gate marked with Mt. Fuji’s name. To the right is a particularly strange statue of a traditional climber from the cult of Fujiko, and in the vicinity, there are a number of commemorative stone tablets left by previous climbing groups.

The next stage of the climb follows a wonderfully paved road with a gentle slope that glides up through a rich pine forest. For wildlife, keep your eyes open and you may catch a glimpse of a monkey, deer, or pack of wild pigs. In fact, a year past a perky baby boar was found stranded in one of the deep canals that run parallel to the road.

If you see one of her cousins attempting to get out, stop and lend a hand. With the sound of cicadas swirling through your ears, peaceful harmony builds with each step upon the asphalt. One can’t help but wonder why such a wide road is here, and so empty of automobile traffic, and then feel glad you are the only one there.

4.5 km after the shrine, the asphalt suddenly turns to brown earth at Nakanochaya, a stopping place for tea and a comfortable resting place for more stone markers. Leaving the heavy buggers with the singing bugs behind, your sweaty hiking boots can finally dig into the soil of Mt. Fuji. About 2km uphill from Nakanochaya the trail passes the remains of Oishijaya, once a lively stopping point for climbers. Though its glory days are past and the roof is where the floor should be, the building is an impressive contrast to a field of blooming mountain flowers and ordered bee boxes nearby.

Continuing upward, the Yoshidaguchi Climbing Trail covers another 2km before hitting Umagaeshi. Many many years ago, it was here that horses could be ridden and where only those on foot could continue along the holy path to the summit.

Today, it has been dutifully restored by local historians and includes a tori gate, stairs, a hut, a parking lot, and statues of monkeys for the kids. Also, during the middle of August, it is staffed by volunteers who offer thirsty hikers free drinks. Just beyond here, the trail turns into a deep trench cut by the footsteps of hikers, eruptions, explosions, and erosion.

The air here is cooler, the earth darker, and the plant life simply exotic to behold. Just as you wonder where the 1st Station could possibly be, it appears around a corner in the form of a boarded-up shack (Dainichido Suzuhara Sengen Shrine) and more commemorative stones amidst a grove of standing pine trees.

Though the shrine appears neglected, it still houses the spirit of Dainichinyorai, and saying hello or leaving an offering can do you no harm. In times past, it is written that many a ritual was held here, but in the 3rd year of Kyoroku (1530) the party must have gotten out of hand. Gutted by a devastating fire, this particular shrine was rebuilt 300 hundred years later during the Meiji Era.

With a little more effort, the trail soon leads up over rocks to the 2nd Station and the tremendous remains of Omuro Sengen Shrine. Today, the main sanctuary of the shrine can be found quite distantly downhill near Lake Kawaguchiko.

This skeletal structure is more than fantastic, however, and the ancient teahouse nearby stands as a testament to the strength of Japanese construction in the face of extreme elements. About 1km uphill and southeast of here is a holy ground for women which, until the 19th Century, was the highest spot that women legally be on Mt. Fuji.

From this holy earth, the trail crosses and is crossed by the hardened lava of past Mt. Fuji eruptions (the last being in 1707). A tip for first-time volcano hikers to keep in mind is this: if the lava is fresh, head downhill in a hurry.

One small kilometer from the 2nd Station, an ugly forest road bisects the trail. Ignoring its presence, cross it and you will be your way again along the Yoshidaguchi Climbing Trail. This section is known as “Yongo Goshaku” which describes the space between the 3rd and 4th Stations. At the former, there is a broken-down tea hut scattered with smashed dishes. In the latter, there is the impeccably clean Gazaishi Sengen Shrine.

The Gazaishi Sengen Shrine has been erroneously labeled by its owner as of the 5th Station of Mt. Fuji, yet it technically is the 4.5th Station. Pondering the significance of this, cast your gaze out over the faux wood fence and enjoy the spectacular panorama (on clear days) or close-up views of the clouds.

With your mind drifting over this vast slope of unharvested trees, feel the emotions of being 2000m above sea level. Also, if you have been lugging a 200-kilo commemorative stone consider this a perfect place to leave it.

Past the Gazaishi Shrine, the clouds come and go amidst the dwindling alpine tree cover and more crumbling huts of days long past. Finally, the trail hits the 5th Station, where tens of thousands of climbers choose to start their push to the summit.

The 5th Station of the Yoshidaguchi Climbing Trail is one part of a “Station” that stretches along a 2km lateral swath of Mt. Fuji near the treeline. The Yoshidaguchi Climbing trail crosses the far reaches of this station at the Sato Mountain Hut and proceeds quickly uphill. For the crowds, a parking lot stuffed with cars, gaggles of tourists, and the Fuji Subaru Toll Road, head to the opposite end of the 5th Station—2 km southeast.

If you are continuing uphill, start hiking to the 6th Station. The 6th Station of Mt. Fuji hosts the Mt. Fuji Safety Guidance Center, a place to pickup information on the climb, rest, or be assisted in case of an emergency. Also, the remains of the old Mt. Fuji Safety Guidance Center reveal the power of a landslide in the recent past. This disaster spared many lives but destroyed some fancy toilets. Further uphill is more of the 6th Station in the form of two mountain huts.

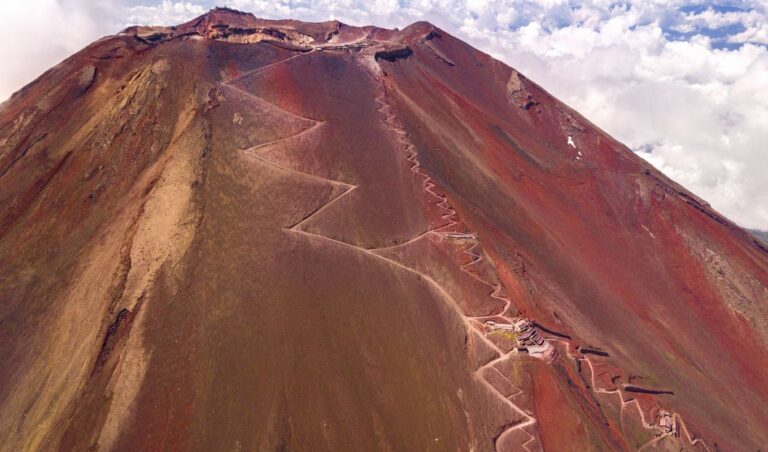

Photo: Mt. Fuji View from the 6th station down

Along the way to the 7th Station, giant metal constructs punctuate the red earth, dutifully keeping the rocks and landslides at bay. In the summer, rare alpine flowers can be seen along this route and should not be picked for souvenirs. As the path turns from dirt to steep, solid stone, hikers hit the bottom of the 7th Station. Like the 8th Station above it, this station stretches vertically upward, with mountain huts nearly on top of each other. A red tori gate marks the true 7th Station.

Photo: Mt. Fuji View from the 7th station

More scrambling over blown chunks of volcanic rock, stairs, and even some sandy trails, and hikers reach the bottom of the 8th station. Looking upward, the yellow characters of the Real 8th Station can be seen (本八合目) a good distance further uphill past many mountain huts. After passing an altitude marker for 3000m, hikers will surely begin to see the affects of high altitude as the oxygen thins and pace slows. Strong winds may also affect climbing here, but determination grows, or lessens depending on intestinal fortitude.

Photo: Mt. Fuji View from the 8th station

With the top of the 8th Station finally behind you, there are a series of switchbacks pushing forth toward the top. On the right side of the trail before the 9th station there is a place where climbers leave their climbing bells and ribbons called “Ishimuro.” Just past Ishimuro is the sole marker of the 9th Station, a lonely unpainted tori gate and the last half-kilometer of the Yoshidaguchi Climbing Trail. During summer nights, the pace here slackens to less than that of a hobbled groundhog, but on a summer day should only take 20 minutes.

Photo: Path to the summit of Mt. Fuji

At the top of the stairs is the summit of Mt. Fuji, marked by a little shrine, stalls, and the crater. With high winds and temperatures typically well below freezing, most hikers take a few pictures, watch the sun, and quickly hike down along the descending trail. Others hike around the crater, pray, eat a meal, use the phone, send letters, or sit and shiver while eating o-bento and wishing they didn’t have to walk all the way down again.

All in all, the Yoshidaguchi Climbing Trail is an experience not to be missed. Fortunately, since the creation of the Subaru Toll Road to the 5th Station (the real one, not the 4.5th), 90% of so-called “Mt. Fuji Climbers” start their journey with the last 6km to the summit, bypassing the greater part of the mountain. This leaves the lower 12km free from crowds and nonsense, and with the exception of the monkey statues, remains true to what the pilgrims of days long past experienced when they climbed the perfect slope of Mt. Fuji.

Fujisan Yoshidaguchi Climbing Trail Map is here: http://www.city.fujiyoshida.yamanashi.jp/div/english/html/images/climbin…